Tags

I’ve been brushing up on the work of Eric S. Raymond, an open source software advocate and author of ‘The Cathedral and the Bazaar,’ in preparation for meeting and interviewing him at next week’s Culture Conference in Philly and Boston.

Raymond has written extensively about the attitudes and ethos of hackers, the mechanisms of open-source development, and the relationship between motivation and reputation in a gift economy.

As I read his stuff, I see a strong parallel between how hacker culture can apply to culture hacking, and functionally accelerate personal and social evolution at scale.

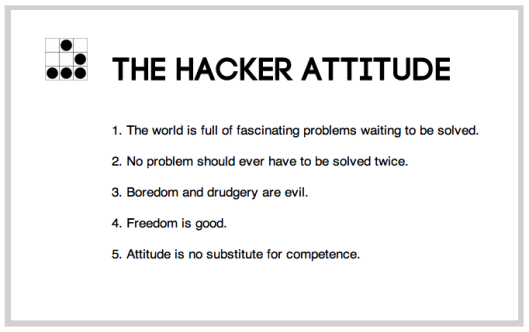

So let’s start with the hacker attitude: (excerpted from Raymond’s essay How to Become a Hacker)

1. The world is full of fascinating problems waiting to be solved.

2. No problem should ever have to be solved twice.

3. Boredom and drudgery are evil.

4. Freedom is good.

5. Attitude is no substitute for competence.

This is apparently the general disposition of the thousands of people voluntarily hacking part-time who built and evolve the Linux operating system, for example.

(note: the definition of ‘hackers’ are “having to do with technical adeptness & a delight in solving problems and overcoming limits,” and so ring true for anyone pursuing mastery in their chosen creative expression… musicians, artists, athletes, scientists, etc)

It seems to be the same disposition among the communities of people talking about intentional lifestyle design – those that want “work” and “life” to not suggest two worlds out of alignment, but rather are working to create a consistent underlying culture that allows each person to bring their gifts and strengths forward regardless of social context.

Software hackers may strive to produce elegant code out of the joy of craftsmanship, to demonstrate excellence at solving a wicked problem, and to garner respect among their peers. Culture hackers want to define the social agreements and communication protocols most likely to lead to human fulfillment, creativity and happiness…. then build the new socioeconomic systems upon that life-enhancing infrastructure.

Then I was reading up about the characteristics of open source development communities:

* code-sharing in order to create the best solution

* user base becomes co-developers – helping diagnose problems, suggesting fixes, and helping improve the code

* release early and often (ego-satisfying stimulation + rewarded by the sight of constant improvement in their work!)

* more users find more bugs

* listen to beta testers, poll them, stroke them when they send in patches and feedback

These same principles could apply when looking to build a co-developer community for cultural evolution, no?

“When you start community-building, what you need to be able to present is a plausible promise. Your program doesn’t have to work particularly well. It can be crude, buggy, incomplete, and poorly documented. What it must not fail to do is (a) run, and (b) convince potential co-developers that it can be evolved into something really neat in the foreseeable future.”

What is the ‘plausible promise’ that makes something like Burning Man work? (note: I’ve still never been to Burning Man! gah!)

And why run an experiment like this only for a week?

I’m going to let this simmer for now, but it seems like there could be a mass collaboration project to evolve the ‘software for our heads.’ How do we fix the ‘bugs’ in human thought and behavior? What is the faulty logic, assumptions, beliefs, or patterns that don’t serve us, or are unlikely to lead to the results and outcomes we claim to want? How do we reprogram that? Is there a shared universal language for it?

—

further reading: The Cathedral and the Bazaar

It would be interesting to get Eric’s take on these:

http://www.forbes.com/sites/venkateshrao/2011/12/05/the-rise-of-developeronomics/

Three-part series on Software Entrepreneurs and other hackers:

http://www.forbes.com/sites/venkateshrao/2012/09/03/entrepreneurs-are-the-new-labor-part-i/

http://www.forbes.com/sites/venkateshrao/2012/09/03/entrepreneurs-are-the-new-labor-part-ii-2/

http://www.forbes.com/sites/venkateshrao/2012/09/04/entrepreneurs-are-the-new-labor-part-iii/

Can you comment on the fact that there is no mention of “design” in the hacker or Open Source credos?

I love that part about community building starting with a plausible promise. Very helpful. Thanks you.

I too feel there is something to be learned from open source software development that can be applied to the broader problem of building the next evolution of our culture but am struggling to see what it is.

PLACING IN CONTEXT: Problem solving, hacking, and local community/culture building are excellent and appropriate tactics. However, elevating them in collective to strategy may be dangerous. The Club of Rome, decades ago, alerted us to this issue and proposed a term, problemateque, to label a strategy that is not exclusively problem/solution or knowledge modeled as only question/answer. The longer term consequences of tactics, and their often unexpected synergies, must be part of strategy design/planning/programming/project-action. Stratagizing can be viewed as a system of meta-projects, which are seldom identified by Here&Now challenges, which are also done by teams. Strategizing generates projects for hidden problems that may be encountered in the future.

One challenge with any analogy to open source software is:

With software programs, it is always possible to test whether the software does indeed “run”.

With cultural programs, they can only be tested in the mess of reality, over long timeframes, with real consequences that may prevent the experiment being repeated.

Which is part of the reason I’m becoming increasingly interested in simulations…

Pingback: Why the World Need Hackers Now: The Link Between Open Source Development & Cultural Evolution

Interesting, I like the hacker attitude. I’ve thought about this concept from a learning perspective but not from a cultural perspective – http://learnstreaming.com/tinker-and-you-will-learn/

This helps expand my thinking and I look forward to following this idea. Thanks

Love the post. please share our hack-the-hack challenge. The best business-culture hack kind and queen will be announced end Sep: http://bizculturehackers.com/hack-the-hack-challenge/

Management mavens and big name consulting actively support hacking in their own domain. http://managementexchange.com/

Pingback: Friday Fabulosity Link Fest | rethinked…*

Reblogged this on Strategy Inc. and commented:

Fascinating read on the Hacker Attitude.